Documenting Anti-Asian Hate Crimes Is First Step to Promoting Mental Health

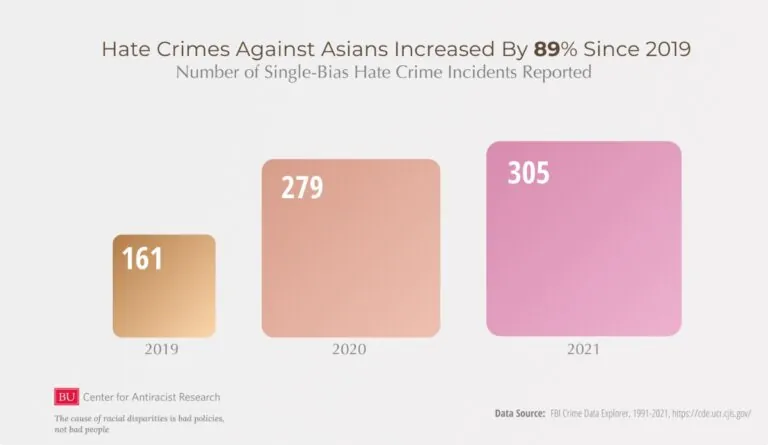

The COVID-19 pandemic was accompanied by an epidemic of anti-Asian hate crimes, with reports of these crimes rising by 89% between 2019 and 2021.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

The COVID-19 pandemic was accompanied by an epidemic of anti-Asian hate crimes. Between 2019 and 2021, hate crimes against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) escalated by 89%. Hate crimes against AAPI have taken many forms, including physical assaults and near-fatal stabbings. Hate crimes do not include other discrimination like being called a racial slur, nor crimes that go unreported.

Racial discrimination can impact health and well-being. Individuals hearing racial threats may become more vigilant and worried about the next occurrence. A study of young adult Asian American females showed that 68% reported that they or their family experienced anti-Asian discrimination related to COVID-19, such as hearing a derogatory comment about Chinese people being the source of the virus. The resulting stress may be one reason why the Asian American females in the study who reported discrimination had more anxiety and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Poor mental wellbeing can also lead to physical health consequences. Stress caused by discrimination may curb practicing healthy behaviors like quality sleep and increase unhealthy coping like substance use.

As the first COVID-19 outbreak was recorded in Wuhan, associations between the virus and China sparked Anti-Asian hate crimes. This connection was strengthened by bigoted remarks by Donald Trump coupled with “lab-leak” theories, suggesting that the virus was released from a laboratory in China. Though the number of COVID-19 cases has decreased dramatically, anti-Asian hate crime rates remain high and racist rhetoric against Tik Tok further feeds the flames of xenophobia.

Underreporting obscures the gravity of this violence. Total counts of recent anti-Asian hate crimes hint at but do not fully show the true severity of anti-Asian racism these past few years. Additionally, when counting hate crimes, the FBI categorizes this violence as single-bias incidents or multi-bias incidents. Single-bias incidents are hate crimes that are solely motivated by a single bias (i.e. race), whereas multiple-bias incidents point to instances in which more than one point of bias is at play (i.e. race and gender). Therefore, anti-Asian hate crimes that are coupled with another source of bias are not reflected in the count. The number of hate crimes reported to the FBI is likely much smaller than the number of hate crimes that actually occur.

Although hate crimes can be reported to any local police department, many non-English-speaking people are not offered appropriate avenues to report victimization, leaving many hate crimes lost in translation. AAPI movement leaders indicate that policymakers can more effectively advocate for changes based on information they receive, underscoring the need to reduce language barriers to reporting.

Strategies to address this gap include having bilingual officers onsite. When necessary, translation services should be provided to ensure victims are aware of their rights and resources. Alternatively, some victims are wary of police and other authorities, and may feel more comfortable disclosing the violence to a community representative instead. Policy changes should ensure victims feel empowered at every stage of the reporting process.

Fortunately, we are better equipped to address the effects of hate crimes because of growing mental health advocacy for the AAPI community. The model minority myth, the idea that Asian Americans achieve above-average success despite economic and cultural barriers, has been widely believed and has obscured AAPI mental health needs. Now, we are beginning to dismantle this notion as we recognize discrimination and its harmful effects on the AAPI community.

Hate crimes are an urgent public health problem; let’s not waste this reminder of the perniciousness of discrimination as we support our Asian American communities.

Databyte via the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research. Infographic created by Yukun Yang.

Public Health Post is collaborating with researchers at the Center for Antiracist Research Racial Data Tracker to produce a series of articles focused on structural racism and health. This is the sixth article in the series.

The goal of the Racial Data Tracker is to collect, analyze, and publicly share data on racial inequities and disparities with communities and individuals interested in using racial data for research, advocacy, education and policy. The data will be available through downloadable data tables, infographics, and interactive visualizations. The project will publicly launch in Spring 2023.