Creating Health is Like Winning at Soccer

As the 2018 World Cup moves toward its finale, it's clear that soccer is the global sport, with an estimated 500 million people playing regularly, or about 5% of the world’s population.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Creating Health is Like Winning at Soccer

As the 2018 World Cup moves toward its finale, it’s clear that soccer is the global sport, with an estimated 500 million people playing regularly, or about 5% of the world’s population. The game is simple: eleven players on one side try to get the ball into the net on the other side. Of the eleven players, only the goalie can use her hands to keep the ball from getting into the net.

Those who are not used to soccer may, reasonably enough, see the goalie as the key to winning. After all the goalie is the last defense, standing between the ball and the net, and in theory a spectacular goalie can stop every shot that comes her way.

But anyone who watches a professional soccer game will notice that the goalie spends most of the game prowling the space in front of her net, exhorting the other ten players to keep the ball away. Why? Well, a good goalie knows that no matter how good she is, she will not be able to keep certain balls out of the net and the team will lose if there are too many shots on goal. Hence it is up to the other ten players to keep the ball upfield to make sure the team wins the game.

What does this have to do with health?

Well, we see soccer as a perfect metaphor for how we generate health. As we have noted many times in this series, health is created by the world around us—by the water we drink, the air we breathe, by an environment that is safe, that encourages exercise, by the healthy food that is available to us, and by social policies that create a world free from violence and inequity. Imagine that those conditions are the ten players on the field. Those players are what moves the ball upfield, what maximizes our chance of winning, staying healthy.

What about the goalie?

The goalie is medicine. The goalie is our last resort—what can restore us to health if we get sick. We obviously want to have a very good goalie, a very good doctor, because we know that, every once in a while, there will be a shot on goal no matter how good the other ten players are. But we also know that if we rely only on medicine we will not be healthy, we will simply be confronting disease after disease, until we lose.

We need a shift in the way we think about health. As in soccer, ten elevenths of our effort should be preventive. Health is not about medicine, our last line of defense. Health is about the politics that create the world around us, about where we live, about housing, transportation, and a livable wage. It is also about medicine yes, but medicine as part of a much larger team of forces that create a healthier world.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

OH, SNAP

More than half of households receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits still report being food insecure, uncertain of having, or unable to acquire enough food because they have insufficient money or other resources. This argues for SNAP expansion: an increase in the benefit amount and/or eligibility for a wider group of households. Gundersen, Kreider, and Pepper calculated a “resource gap” of how much additional income households would need in order to be food secure. The average weekly resource gap was $41.62 for food-insecure SNAP households. The authors suggest that there would be a 100% reduction in the national food insecurity rate if we are willing to spend an additional $20.1 billion for current SNAP participants and $7.1 billion for currently SNAP-ineligible households.

PAY ME, VACCINATE ME

Medicaid pays physicians far lower fees than Medicare or private insurers. The gap in fees is particularly large for immunization services. This study examined the relationship between Medicaid vaccine administration fees and immunization of 1.7 million Medicaid-enrolled children in eight states. For every $10 increase in the payment amount, the probability of children making more than one vaccination visit increased by 7.2 percent. Routine childhood immunization is among our most cost-effective disease prevention programs. More generous Medicaid reimbursements would improve vaccination rates to low-income children.

CLICK IT OR TICKET

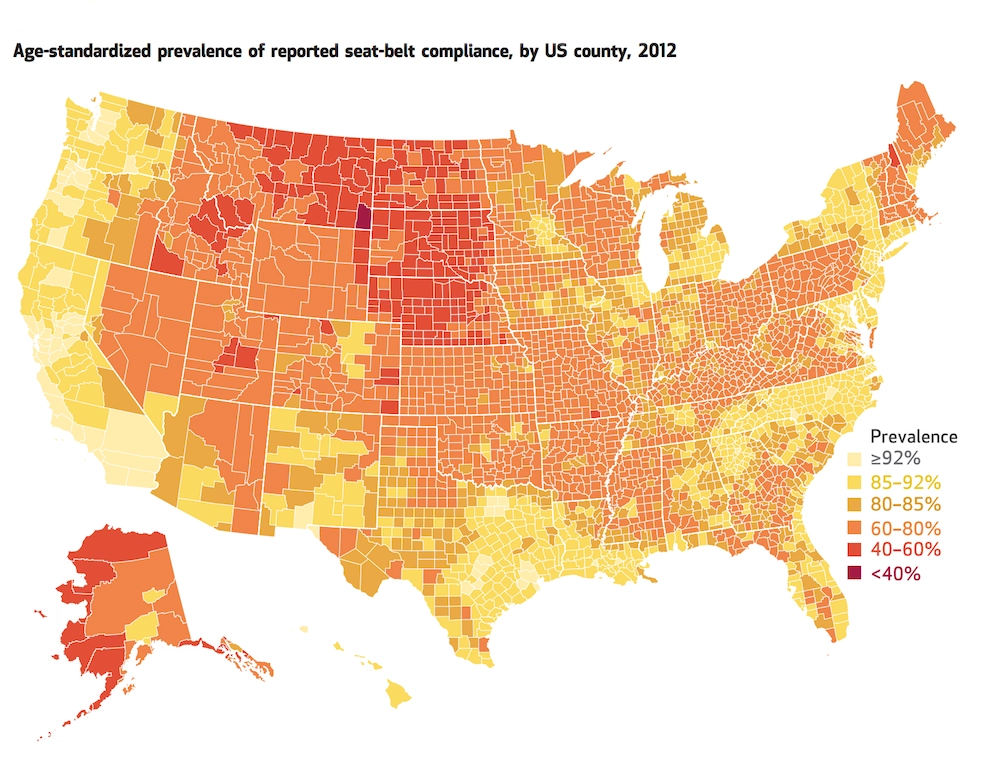

Research shows that seat belts result in a decrease of 45-60% in fatality risk for front seat passengers. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that seat belts saved more than 12,500 lives in 2013.

Seat belt usage in the United States increased from 79.2% in 2002 to 85.9% in 2012, but usage is still lower than in other high-income countries.

Approximately half of the 32,000 motor vehicle crash fatalities in 2013 in the US did not use seat belts. There was a 7.2% increase in fatalities in 2015, the largest percentage increase since 1966. This recent uptick in motor vehicle fatalities is cause for concern and is reason to re-examine seat belt policies.

A study in Health Affairs by Jacob Sunshine and colleagues shows the wide variance in seat belt usage across the country. Noncompliance rates were high in the 15 secondary enforcement states, where police officers are only allowed to write seat belt citations when the vehicle is pulled over for another traffic violation. High compliance is found in states that have primary enforcement laws, such as North Carolina, California, and Oregon.

This is not just a question of urban vs. rural areas. Rural areas, in general, have a lower rate of compliance than urban areas, but rural areas in primary enforcement states have a higher rate of seat belt usage than rural areas in secondary enforcement states.

—Qing Wai Wong, PHP Fellow

Map from Health Affairs Vol. 36, No. 4: Seat-Belt Use In US Counties: Limited Progress Toward Healthy People 2020 Objectives, by Jacob Sunshine, Laura Dwyer-Lindgren, Alan Chen, and Ali H. Mokdad. Published April 2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1345