Allies in Criminal Justice Reform

Massachusetts is one of only four states that has not implemented medical parole, which allows allows incarcerated individuals with terminal illness or permanent incapacitation to return to their communities.

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

Locked away and out of sight, millions of incarcerated Americans might be easy for society to forget. They are not hidden, however, from the ravages of aging, health disparities, and chronic diseases. Challenging diagnoses, such as advanced cancer, end-stage congestive heart failure, and severe respiratory illness, are difficult for all patients to cope with and manage; behind concrete walls and barred windows, effective long-term disease management can be nearly impossible.

In an attempt to find more reasonable ways to address the needs of incapacitated individuals who are incarcerated, most U.S. states (46 plus the District of Columbia) have some version of a medical parole bill in place. Medical parole, sometimes called compassionate release, is the mechanism by which certain individuals faced with terminal illness or permanent incapacitation while incarcerated can transition back to their communities, where they can receive more cost-effective and appropriate care. Given their terminal diagnosis and inability to care for themselves, they no longer pose a threat to society. Different states have implemented different versions of medical parole legislation, although the number of patients these laws apply to varies wildly due to various eligibility criteria. Nevertheless, Massachusetts is still one of four states in all of the U.S. that has not implemented a medical parole bill.

Through clinical experiences in several Massachusetts correctional facilities, members of the group Harvard Medicine Indivisible (HMI) have seen first-hand what this reality can look like for people behind bars, including those afflicted with severely debilitating non-terminal illnesses and cognitive impairments. Students and clinicians have met incarcerated patients with such advanced dementia that they cannot bathe or use the toilet on their own. Some require advanced attention from correctional and medical staff, which is very resource-intensive and expensive. Individual patients can sometimes require the equivalent of nearly one full-time correctional officer around the clock to appropriately address their needs. There has been at least one situation in which a patient could not always remember which correctional facility they were in, and it was not clear that individual always realized they were incarcerated. This person had extremely limited access to support from family members and would likely spend the rest of their life in a single cell, punished for a crime they may not even remember.

…members of HMI’s Mass Incarceration and the War on Drugs Working Group (MIWOD)—composed of physicians, public health professionals, researchers, and health workers—expressed a shared moral responsibility and drive to speak up for our most vulnerable patients and community.

Organizing in Massachusetts, members of HMI were trained from the group’s early inception by the long-time organizer and professor, Marshall Ganz. Rooted in this leadership framework, members of HMI’s Mass Incarceration and the War on Drugs Working Group (MIWOD)—composed of physicians, public health professionals, researchers, and health workers—expressed a shared moral responsibility and drive to speak up for our most vulnerable patients and community. To this end, the group organized one-on-one meetings with legislators and stakeholders to discuss key points regarding medical parole legislation based on lessons learned from other states and past efforts to negotiate legislation in MA. The HMI group also gathered testimony and individual stories that support the implementation of medical parole.

Three important aspects of patient eligibility were identified as being crucial for the legislation to be effective. These findings were shared with the state and district representatives and are summarized below.

First, medical parole policies should not require a terminal prognosis with a time limit, such as the 18-month life expectancy required in the proposed Bill S.874 or the 12-month alternative in Bill H.3494. As studies show that physicians are poor prognosticators (often over-estimating life expectancy), provisions requiring physician prognostication are both inaccurate and limit the number of inmates who could benefit from this intervention. A 12- or 18-month restriction on prognosis would place physicians in a difficult position and needlessly restrict the utilization of medical parole.

Second, medical parole should be available to all incarcerated individuals who have lost their ability to care for themselves, rather than only those who are permanently physically incapacitated. The clinicians in the group realize that the diagnosis of “permanent incapacitation” is difficult to make. Rather, the “loss of ability for self-care” is a more specific metric that practitioners can more reliably and accurately comment on. For instance, restricting permanent incapacitation to physical disability, as written in S.874 and H.3494, denies access to patients with severe dementia who may not even understand the reasons for their incarceration. Furthermore, from a cost-saving perspective, the loss of a patient’s ability to care for him- or herself is a turning point where both the state and the patient would most benefit from access to home healthcare, rather than require persistent, expensive, and often indefinite attention from guards and staff.

Third, we as a group applaud the bills S.874 and H.3494 for not excluding any patients on the basis of the crime for which they were convicted. We felt that excluding a patient with severe dementia or end-stage cancer on the basis of a violent crime is not sound public safety policy; it merely denies severely ill patients the ability to uphold their dignity through standard-of-care palliative care in the community. Keeping incapacitated individuals in prison—even those who committed a violent offense, often decades earlier as these crimes tend to carry long sentences—is not sensible public safety policy because they can no longer cause harm to society and, ostensibly, are no longer able to effectively “rehabilitate” (i.e., the purpose of prison). Second, the humanitarian argument in favor of medical parole contends that all people—including incarcerated individuals—have a human right to dignity and to die in the company of their families and loved ones.

As healthcare professionals, physicians, educators, and public health workers, we believe that medical parole is ethically necessary to uphold human dignity. End-of-life care exists to maintain human dignity by providing meaning and purpose, autonomy, and attention to spiritual and emotional needs. For incarcerated patients, access to this standard of care is not only an ethical imperative, but also a constitutionally protected right.

These many one-on-one meetings and discussions with representatives, advocacy groups, and our broader healthcare constituency have fueled the urgency behind HMI’s MIWOD working group’s commitment to continue organizing around this topic. It is through this engagement and conversation that we have been able to see where and how our voice as health professionals could be useful, turning resources into power towards the achievement of common goals.

Finally, we urge health professionals and care workers to join in standing for the passage of a medical parole bill as well as effective criminal justice reform in MA by bringing together our experiences and speaking up along with state representatives toward legislation that upholds human dignity and attempts to reduce structural injustice.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for Rebecca Abelman and Andreas Mitchell for their review and comments, and all members of Harvard Medicine Indivisible.

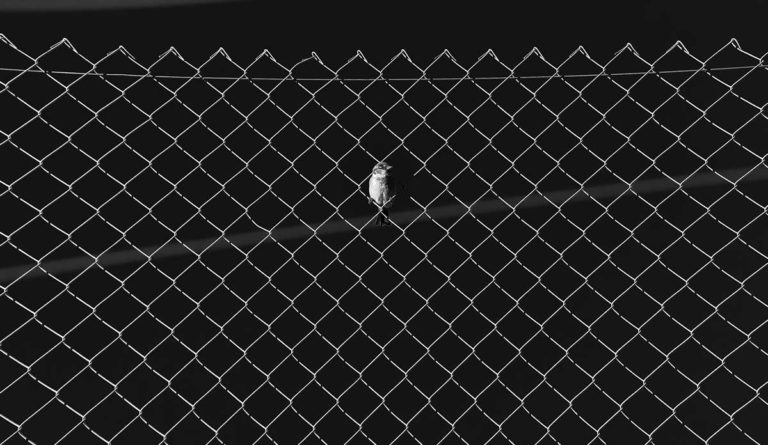

Feature image: Hernán Piñera, Grid, used under CC BY-SA 2.0