The Promise of Palliative Care

As the population ages, patients seeking care for multiple chronic conditions has become the norm.

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

The Promise of Palliative Care

As the population ages, patients seeking care for multiple chronic conditions has become the norm. Sixty percent of Americans die following a prolonged illness; the “compression of morbidity”—the burden of disease and disability limited to a brief time before death—has not yet become a reality in the United States. The care of persons with serious chronic illnesses like cancer and heart disease then often falls to families whose members absorb the burden of a loved one’s needs, with negative effects on their work, finances, relationships, and community engagement.

Palliative care focuses on improving the quality of life for people with life-threatening illnesses by involving a team of nurses, doctors, social workers, and clergy in a care plan. From its inception nearly fifty years ago, palliative care was meant to provide a system of support for the families of the ill, as well as the patient. Hospice care—in dedicated units and in services at home—has been slowly expanded over the past two decades, but the increasing percentage of patients who use hospice for less than seven days suggests that the full benefits of end-of-life palliative care are not being realized.

Meanwhile the use of unwanted aggressive end-of-life care, often inconsistent with patient preferences, remains pervasive. Palliative care programs were designed to help clarify patient wishes, relieve suffering, and improve quality of life throughout an illness, not just at the end of life. Most palliative care is now delivered during hospitalization, when it should be shifting to the community earlier, relieving families from carrying the burden alone.

Community services are currently limited by small numbers of workers and misdirected reimbursement mechanisms; corrective policies are slow to materialize. The Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act has finally been approved by the House of Representatives and has recently moved into Senate subcommittee for review. It would increase the number of professionals trained in palliative care techniques.

But there are other obstacles to progress. The primary one is cultural. When the co-founder of Google announces that he hopes to “cure death,” when we believe immortality is achievable through bio-hacking, when the entrepreneurial class chases anti-aging diets, exercise regimens, and technologies, palliative care becomes an admission of failure. Just as Americans have low rates of completing living wills and choosing medical surrogates, they receive few medical referrals to palliative care; doctors notoriously overestimate how long terminally ill patients will live.

Palliative care was not created only for the terminally ill. It can be administered to those who will eventually be cured of an immediate life-threatening condition. But it must equally be delivered to family caregivers. The public health issue involves not only patients, but also their families who face material and psychological challenges and require a comprehensive strategy.

For any public health strategy to be effective, it must be supported by government policies and insurer incentives, but owned by the community, which must continue to ask for help in designing and paying for high-quality palliative care for patients and their caregiving families.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

GOOD DEALS ON MEALS

Government provision of meals at school for low-income students began in 1946 and seventy years later more than 30 million students received at least one free lunch at more than 100,000 schools across the United States. Still, a high proportion of eligible children do not participate in the National School Lunch Program or School Breakfast Program. This study cites three main reasons. First, receiving free or reduced-price meals can carry a stigma, so some children or their parents may not want to participate. Second, many schools do not serve breakfast and, hence, even eligible children at those schools cannot participate. Third, despite being enrolled, some children do not always eat the meals provided. Food available at school decreases the prevalence of food insecurity among households with children in school by 2.3 to 9.0 percent. During the summer, when most children do not participate in school meal programs, the extent of food insecurity increases.

YOUR JOB AND YOUR LIFE IN THE OPIOID ERA

Opioid deaths and emergency department visits are predicted to increase when unemployment rates increase. A one percent increase in unemployment at the county level can be expected to result in a 3.6% increase in opioid-involved mortality. In the current opioid crisis, local economic downturns may have dramatic effects on mental health and overdose risk.

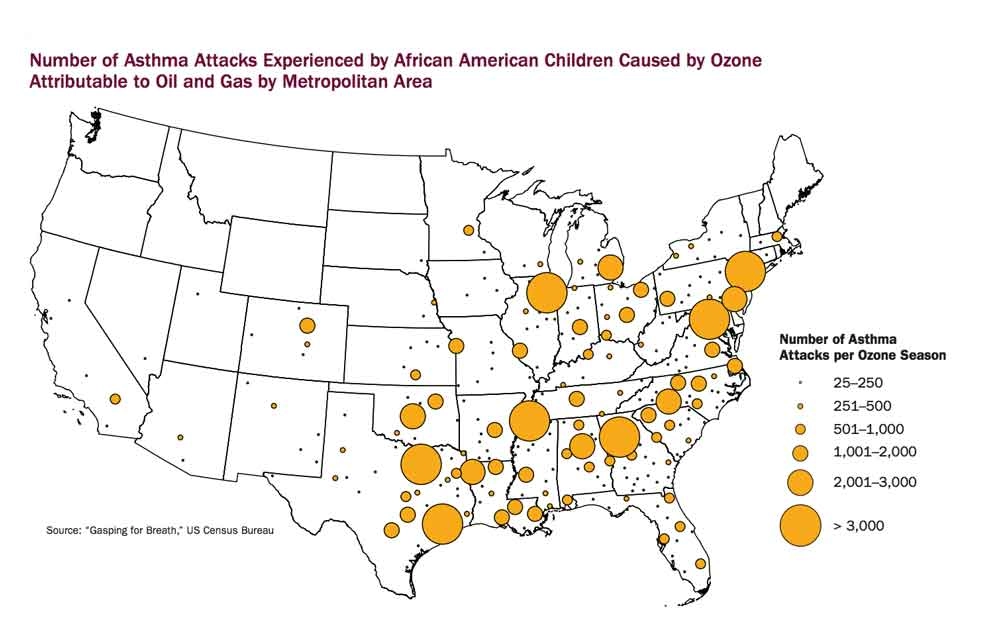

ASTHMA ATTACKS AMONG AFRICAN AMERICAN CHILDREN

More than 1 million African Americans live within a half mile of a natural gas facility. This proximity is associated with an increased risk for negative health effects such as asthma, headaches, nose bleeds, and throat and eye irritation caused by air pollutants. African Americans are 75% more likely to live in a neighborhood next to a polluting facility, or “fence-line” community, than other racial groups.

In 2017, Lesley Fleishman of the Clean Air Task Force and Marcus Franklin of the NAACP reviewed the impact pollution from oil and gas facilities has on the health of African Americans living in fence-line communities. Using data collected by the Clean Air Task Force and the US Census Bureau, they show that an estimated 138,000 African American children suffer annually from asthma attacks caused by oil and gas pollution. This makes up 18.5% of the total 750,000 asthma attacks experienced by children nationally and contributes to the 101,000 school days African American children miss each year.

The map shows the areas of the country where children are at highest-risk of asthma attacks associated with pollution exposure. The larger the circle, the more children affected. Black children in Louisiana, Georgia, New Jersey, Illinois, Tennessee, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Texas experienced asthma attacks most frequently. Metropolitan areas around Dallas, Atlanta, Washington D.C., New York, Houston, and Chicago recorded over 3,000 asthma attacks per year. The Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan areas had the highest number of attacks (8,059). Exposure to pollution and asthma cases can be prevented through investments in renewable energy, better residential zoning policies, and air pollution monitoring. Activism in communities along the fence-line will also be critical to tackling the environmental injustice being experienced in communities of color. —Erin Polka, PHP Fellow

Map: Fumes Across the Fence-Line, The Health Impacts of Air Pollution from Oil & Gas Facilities on African American Communities, NAACP and Clean Air Taskforce.