A Party Trick

Conflation of health and healthcare has resulted in an indefatigable investment in healthcare, per Michael Stein and Sandro Galea in The Public's Health.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

A Party Trick

Here’s a game you can play. At your next dinner party or discussion with friends at a bar, start a conversation about how to make Americans healthier. You can talk about anything you wish: the fact that health in America is getting worse, that the opioid epidemic has led to a life expectancy decline, or that firearms are a health problem. When you start the conversation, start a timer.

The object of the game: to see how long it takes for someone in the conversation to use the word “healthcare” interchangeably with health.

We have played this game many times and are confident in saying that the end of the game will come within 5 minutes. It never takes longer for some to inadvertently say “healthcare” when they mean “health.”

The reader of The Public’s Health knows that health and healthcare are very different things. Health is a desired state of wellbeing that allows us to do what we want to do, that has us living full, rich lives, achieving whatever potential we wish to achieve. Healthcare is the system that aims to restore us to health when we get sick. It is what we Americans spend enormous amounts of money on, often at the expense of health.

We argue that the conflation of health and healthcare is not without consequence. In fact, we’d say this conflation fundamentally affects the health of our country. When we think that health and healthcare are synonymous, we do not stop to ask ourselves: how are we doing in investing in early childhood education, parks and recreation, prevention of suicide and substance use, gender equity, and clean air, examples of forces that ultimately create health? If we do not ask how we are doing in these areas, if we do not invest in them, this underinvestment results in our collective poor health.

The conflation of health and healthcare has resulted in a one-sided, indefatigable investment in healthcare. Yet this focus on curative medicine is not improving our health. We should be focusing on health, on keeping us healthy to begin with. And to do that we need to better tell the stories of how health is generated. We should change what we talk about when we talk about health, one dinner party, one bar discussion at a time.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

DRIVING WHILE HIGH

For all its underrated problems, marijuana’s greatest risk may be its association with traffic accidents and fatalities. The prevalence of drivers testing positive for marijuana has increased by almost three times over the past decade, and it continues to rise. These researchers had Facebook users complete an online survey (average age 24, 44% women) about their marijuana use in the past month. Nearly half reported driving high and three quarters reported being a passenger of a driver who was high. Over 60% of respondents felt in control of their driving despite using. Lower rates of driving following alcohol use are reported by young adults. The risks of driving under the influence of marijuana are not yet affecting young drivers’ habits.

HOUSING AND EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT SHELTER

Until recently, Massachusetts had one of the top state housing assistance programs in the United States for displaced families and children. In 2012, however, the state’s housing policy underwent changes, requiring shelter-seeking families with children to provide evidence they have stayed somewhere “not meant for human habitation.” Other eligibility criteria for shelter intake include having faced domestic violence, natural disasters, and no-fault eviction. Emergency rooms offer not only safety, but also discharge papers that could count as such proof of housing needs.

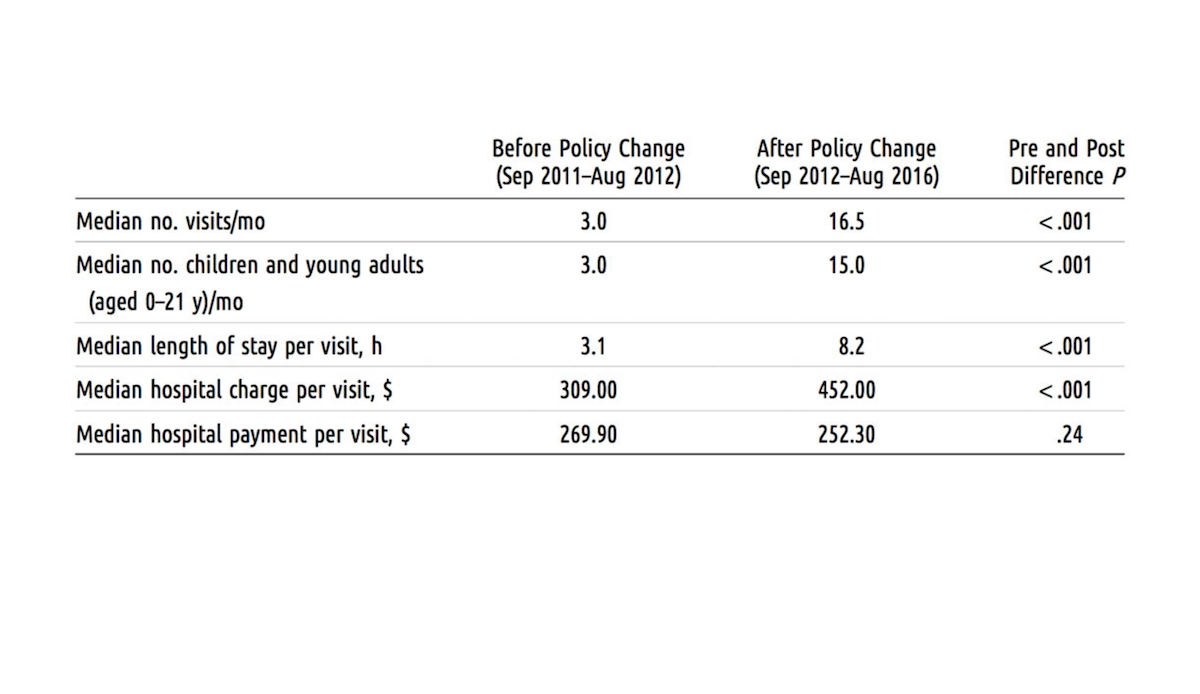

Kanak and colleagues recently observed how often children and young adults used the emergency department as shelter, comparing trends before and after the 2012 policy change. The researchers used medical records of youths below age 21 who visited a Boston hospital’s pediatric emergency room between Sept. 2011 and Aug. 2016 and complained of or were billed for homelessness.

As the figure above depicts, they found the median visits per month increased drastically from three visits before the policy change to 17 visits after the policy change. Most of the children observed were 12 years or younger. The emergency department’s costs and total hospital charges over the five-year period summed to nearly $580,000; only about $19,000 of that amount accrued before the policy change.

The researchers also found that more than 8,500 emergency department hours and $200,000 of Medicaid funds were used, and they suggest that this money would have been better spent to fund housing solutions. The University of Illinois Hospital, for example, helps displaced people who continuously present to the emergency department by paying their rent.—Sampada Nandyala, PHP Fellow

Table from “Trends in Homeless Children and Young Adults Seeking Shelter in a Boston Pediatric Emergency Department Following State Housing Policy Changes, 2011–2016,” Mia Kanak, Amanda Stewart, Robert Vinci, Shanshan Liu, Megan Sandel, American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 8 (August 1, 2018): pp. 1076-1078.