Weathering the Workforce

Now is the time to start educating the health care workforce about the risks of climate change and how to reduce them.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

Eight years ago, Hurricane Sandy pummeled New York City. Sandy was a “superstorm” spanning 350 miles, or the distance from Boston to New York and back again. Its power raised a storm surge of nearly 14 feet at the southern tip of Manhattan. Some 8.5 million people in more than 10 states lost power as a result.

The most iconic blackout darkened Manhattan south of 34th street. In it was NYU Langonne Medical Center and its neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). NYU Langonne’s two backup power systems failed. Over 3 hours, 19 premature infants, many so underdeveloped that they could not breathe on their own, were evacuated. Residents and nurses had to write patient summaries while holding flashlights. To get the babies to ambulances awaiting them on the street, hospital staff carried them down nine flights of stairs.

Nurses, doctors, and staff were called to perform herculean and heroic tasks beyond their scope of training. If the circumstances of the NYU Langonne NICU evacuation were exceptional, we might not consider the need to better prepare health care providers for them. But climate change has made disasters like Sandy more common, and more health care providers are having to improvise their way through weather-related crises.

The need for a climate-ready health care workforce goes beyond facility preparedness planning. Heat waves, already more common and severe because of climate change, can land vulnerable populations, including children, older adults, and people with chronic medical problems in the hospital. Taking certain medications may increase the chances of getting sick during heat waves, too. More people already die each year from heat than all other natural disasters combined. Better counseling from providers about this risk might help patients access cooling stations and prevent a crisis. Now is the time to start educating the health care workforce about the risks of climate change and how to reduce them.

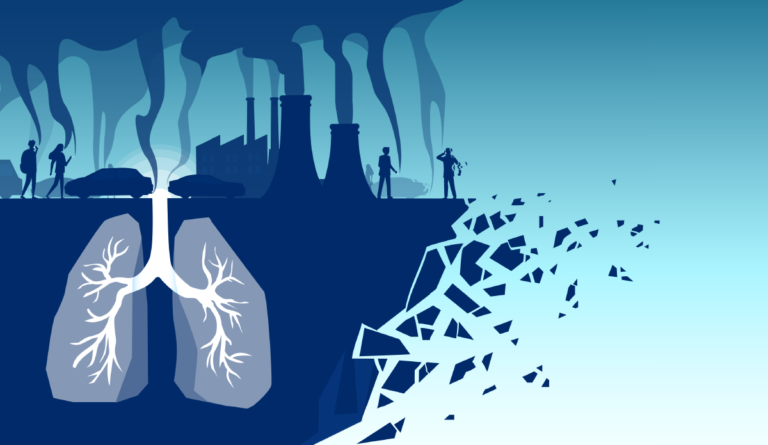

This year’s wildfires in the West, also fueled by climate change, have made air quality in American cities the worst in the world. Because climate-related topics are rarely if ever discussed in medical and other health care training programs, providers have had to scramble to find and deliver useful guidance to patients and families about how to protect themselves.

With better preparation and actions that eliminate the greenhouse gases that drive climate change, we can provide for better health today, protect the most vulnerable people in our communities, and provide for a more just and sustainable future.

With each passing year, calls to better educate health care workers about climate change routinely run into concerns about available time to do so. At the same time, few are knowledgeable enough about climate change to build it into the curriculum. Overcoming these obstacles will require innovative approaches.

In-person learning is blossoming. Nurses have been at the forefront of climate and health advocacy and, no surprise, nursing schools have led the way on climate education, some with dedicated programs on the topic.

Many medical schools, residencies, and even fellowships, like the one we co-sponsor, have started to focus on climate change. I recently published with colleagues from medical schools across the country the first curriculum framework for teaching medical residents about climate change, health, and health care delivery. Opportunities are growing for clinicians to learn more about the relevance of climate change to clinical practice. The Health Effects of Climate Change is a free, open, online course that has already been taken by more than 100,000 students, many of them in health professions.

The path to a climate-ready workforce — one that can meet the challenges of hurricanes, fires, heat waves, power outages, and other threats — is advancing. But there’s a long way to go. Funding to support research on climate change and health and educational programming is stunningly sparse given the scope of the problem. By the NIH’s own accounting, only 0.05% of its $42 billion dollar budget is spent on climate change. More support must come. With better preparation and actions that eliminate the greenhouse gases that drive climate change, we can provide for better health today, protect the most vulnerable people in our communities, and provide for a more just and sustainable future.

Photo via Getty Images