Under-Monitored, Over-Exposed

Regulatory monitors are the gold standard for collecting air quality data, but marginalized communities have fewer monitors than White areas.

Read Time: 2 minutes

Published:

From asthma to heart disease to premature death, air pollution takes a heavy toll on human health. Yet the communities most at risk often aren’t fully accounted for in the data that shapes environmental policy and intervention efforts.

In the U.S., industrial sites, highways, and other sources of pollution are more often built in communities of color. These same communities are also less likely to have air quality monitors.

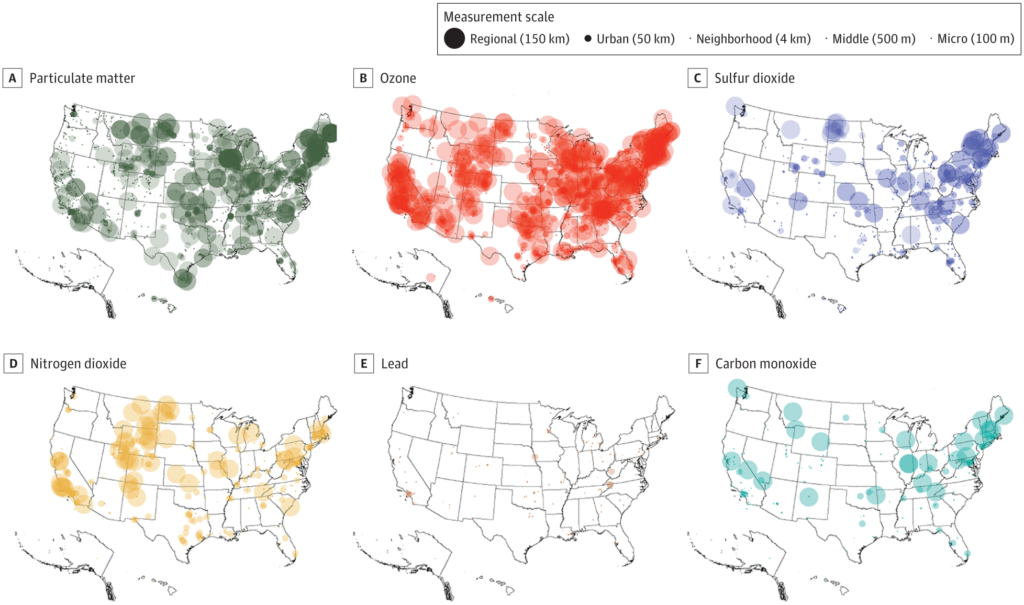

In a new study, Brenna C. Kelly and colleagues mapped the locations of over 7,700 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) air quality monitors and compared them to neighborhood demographics at the census block level. (Census blocks are about the size of a city block, although they are larger in rural areas.) These monitors track pollutants, including particulate matter, ozone, and carbon monoxide.

The data revealed a clear and troubling pattern: areas with more people of color had fewer air pollution monitors compared to predominantly White areas, even after accounting for population density. This disparity was especially pronounced in areas with larger proportions of American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander residents.

Even small increases in the percentage of these populations were linked to fewer monitors. These gaps matter because both groups are already at higher risk for heart disease and asthma compared to White people.

Air quality is hyperlocal. Conditions can vary dramatically from one street to the next, so monitoring must be precise. Sparse monitoring can underestimate people’s true exposure to air pollution, making air quality appear better than it actually is. Inaccurate data can misguide policymakers’ decisions, resulting in underinvestment or poorly targeted interventions that leave the most vulnerable communities behind.

Amid ongoing funding cuts, the EPA continues to monitor air quality—but coverage remains uneven. To expand data collection coverage, the agency could use satellite technology or low-cost sensors. Both, however, have limitations: low-cost sensors are precise, but not consistently accurate; satellites have better accuracy, though less precision, since they sample air throughout the atmosphere, rather than specifically at the ground level.

Regulatory monitors remain the gold standard for collecting pollution data. Expanding monitor coverage, particularly in historically marginalized communities, is critical to address disparities and ensure that every community, regardless of racial or ethnic composition, has the right to breathe clean, healthy air.