Parks and Privilege

The city of Los Angeles is a prime example of disparities in access to healthier, greener urban development. Initiatives such as the Land Trust’s project, known as “Transforming Inner-City Lost Lots” (TILL), empower low-income communities to take the “greening” of their neighborhoods into their own hands.

Read Time: 3 minutes

Published:

Over a half a century ago, city centers flourished. Factories had just experienced the booming demand of World War II and, without more reliable transportation options, workers lived close to their jobs. But when the war ended, a shift away from manufacturing brought rapid change to the structure of urban communities. City folks moved to the suburbs in droves, and tens of thousands of vacant lots were left behind.

As communities deteriorated, so did their residents’ health. With these vacant lots came increased stress, crime, and substandard housing. Access to gardens, parks, recreational spaces, and even fresh fruits and vegetables all became limited to the privileged. Today, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status still tend to determine the availability of green spaces and the many health benefits associated with them.

The city of Los Angeles is a prime example of disparities in access to healthier, greener urban development. A 2016 report by the L.A. Neighborhood Land Trust, “Vacant Lots and Park Equity in Los Angeles: The Problem is the Opportunity,” found that low-income communities of color lack quality parks.

The misuse of vacant lots presents further challenges. Crime and the dumping of waste, for example, are “barriers to physical activity, social cohesion, civic disengagement, and neighborhood pride.” Inequities in park space, quality and access are compounded by challenges to maintaining safety and sanitation and building amenities.

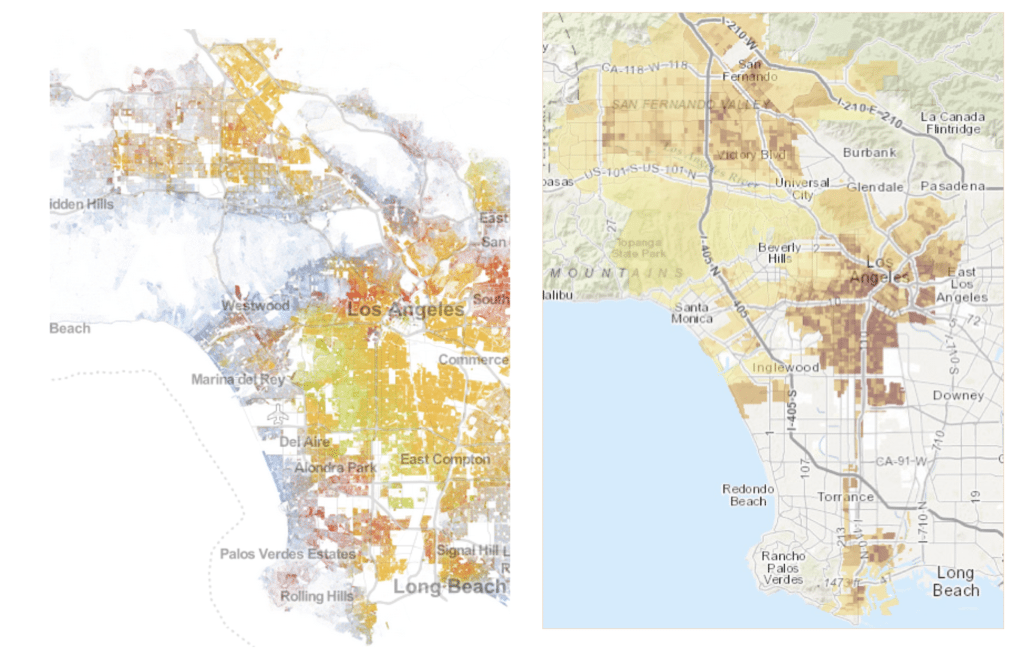

The maps of the city of Los Angeles above colorfully illustrate this disparity. On the left, each dot represents a single person, and the color of each dot represents their race or ethnicity. The map on the right was developed by the University of Southern California’s Spatial Sciences Institute (SSI) in partnership with the Land Trust’s inventory of vacant lots. It layers data of population density, federal poverty levels, median income, age, child physical fitness, and ethnicity to illustrate priorities in vacant lot development.

The Land Trust interprets the deeper shades of red as areas of untapped opportunity: “The higher the score, the higher the need and thus the greater the impact if the vacant parcel were to be converted to green space,” the report says.

The Land Trust’s project, known as “Transforming Inner-City Lost Lots” (TILL), reached out to four “park-poor” communities to find out community members’ priorities, needs, ideas, and hopes for the open spaces. What they found was a “resounding need to connect the development of these spaces to community economic empowerment,” with suggestions for farmer’s markets, safe spaces for local vendors, youth resource centers, and employment with Parks and Recreation departments. Concern for and recognition of the challenges surrounding environmental pollution did not dull excitement for recreation and cultural uses. Ideas included “skate parks, outdoor gyms, parkour parks, botanical gardens, bike garages, public forums or free speech areas, social justice theaters, graffiti hubs, and outdoor amphitheaters.”

With information, support, and advocacy, initiatives like TILL empower low-income communities to take the “greening” of their neighborhoods into their own hands.

Feature image from “The development of a model of community garden benefits to wellbeing” by Victoria Egli, Melody Oliver and El-Shadan Tautolo.