Neighborhood Environmental Injustice

Neighborhoods experiencing environmental injustices, such as high levels of air pollution, are associated with poorer health outcomes.

Read Time: 2 minutes

Published:

Residents of South Tucson, a predominately Hispanic city in Arizona, are acutely aware of the problems with their water. Hazardous waste from aviation and military operations seeped into aquifers from the 1940s until the mid-1970s. The affected groundwater wells were shut down in 1981 and are still toxic today, despite long-term cleanup efforts funded by the Environmental Protection Agency. More recently, PFAS – a forever chemical – has been found in the current water sources. These contaminants have likely caused cancer and other health conditions among residents for the past three decades since the area switched water sources.

South Tucson’s contaminated water is not a unique story. Numerous disregarded neighborhoods have been exposed to harmful environmental conditions, leading to detrimental health effects for their residents. Flint, Michigan and “Cancer Alley,” Louisiana are best known among a terrible list. Ongoing underinvestment in such neighborhoods by local, state, and federal governments has allowed these conditions to persist. The environmental justice movement recognizes how the intersection of race and other systemic barriers impact environmental and human health.

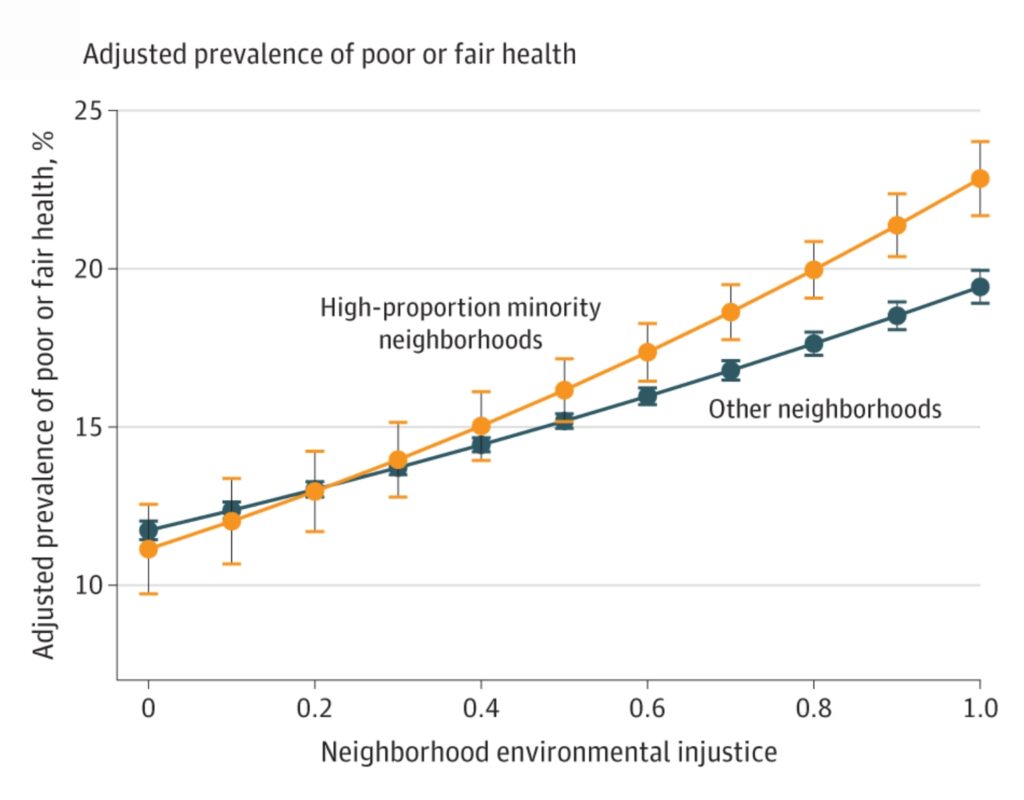

Vishal Patel and colleagues used 2020 census-tract data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Environmental Justice Index and PLACES database to evaluate if environmental injustice scores and health outcomes are associated. The Environmental Justice Index measures a combination of environmental hazards and social factors, such as poverty and access to health care. The PLACES database provides estimates of health outcomes.

The graph above illustrates that neighborhoods with higher levels of environmental injustice are associated with more health outcomes reported as “poor” or “fair.” This correlation is stronger in neighborhoods with a high-proportion minority population.

The researchers conclude that living near air pollution and toxic sites is linked to worse health outcomes. To address this issue, state and federal policies are needed to intentionally address the social factors contributing to environmental injustice in minority neighborhoods.