How Political History Shapes Environmental Health Action

Public health activism in two Massachusetts communities looks different as politics and power influence action related to traffic-related air pollution.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Community Assessment of Freeway Exposure and Health (CAFEH) is a community research partnership that coalesced in 2006 in response to resident concerns about the health risks of living near the Interstate 93 (I-93). The Somerville Transportation Equity Partnership engaged university researchers to provide technical support for a lawsuit. What emerged was a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences funded research partnership to study the health effects of living near the highway. The partnership has since systematically documented associations between cardiovascular disease and ultrafine particle (UFP) exposure.

Traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) is a complex mixture of gaseous and particulate pollutants found in vehicle emissions. CAFEH has identified viable TRAP mitigation strategies to reduce exposure. Strategies include in-home air filtration, closing windows and timing outdoor activities to coincide with periods of low traffic. State and municipal strategies include changing building codes, land use, and transportation infrastructure, which require policy advocacy.

We studied how CAFEH partners are organizing to address the effects of odorless, colorless toxic UFPs, in two communities alongside I-93, the City of Somerville and Boston Chinatown. Somerville and Chinatown both fought steadfastly against the construction of I-93. Yet each lost segments of their communities to the highway and contend with TRAP related health risks. Present-day approaches to public health activism in Somerville and Chinatown are quite different. Findings highlight the role politics and power, play in influencing TRAP related public health action.

Somerville

Diversity in Somerville is not apparent at first glance. Those new to the area might characterize Somerville as a progressive upper middle-class white community, which runs contrary to its working-class roots. Ostrander describes Somerville in the late 1800s as a city run by Yankee Aristocrats on the backs of Irish bricklayers. In the early 1920s the Irish gained political power and new immigrants from Italy and Portugal took their place at the bottom of the economic ladder, fighting for access to political power. As such, Somerville has a rich community action history. In the fight to stop I-93, residents marched, canvased, and lay down in the mouth of a bulldozer.

Today, those once marginalized hold local political power and the approach to public health action has been top-down. It has involved working with municipal officials and elected state representatives to pressure transportation leaders. Partners have leveraged ties with local officials and broken promises from the State related to building noise barriers. Early efforts related to TRAP and public health action centered on engaging the voices of Haitian, Brazilian and Salvadorian immigrants in planning discussions. This was followed by a focus on noise barriers, which reduce but cannot eliminate TRAP exposure. Community partners leveraged their relationships with academic researchers to monitor noise and air pollution in the neighborhood, creating an evidence-base for local and state advocacy efforts.

Chinatown

Boston Chinatown has experienced successive phases of transformation, first through urban renewal, which razed hundreds of housing units for highway construction, then through expansion of the Tufts University Medical School and Medical Center, and most recently with a massive influx of luxury and market rate high-rise development. Each of these phases has brought increased traffic.

Whereas Somerville is a municipality with its own government structure, Chinatown is a Boston neighborhood. In Chinatown, gaining access to political power has looked quite different. The neighborhood has been historically marginalized, leading community leaders and activists to cultivate a bottom-up, grassroots approach to engaging residents and advocating for inclusion. Chinatown employs both community development and social action approaches to organizing, contesting policy and practice to address residents’ priorities. This long history of social action has contributed to a highly organized community infrastructure, including block captains and base-building, that are effective due to strong social capital and community cohesion.

Chinatown residents were actively engaged in discussions about TRAP; however, affordable housing, as well as safe streets for walkers, preserving cultural resources, and quality open spaces emerged as pressing concerns in meetings. This led to the integration of TRAP mitigation strategies in a broader community planning process, associated with the development of a community-led Master Plan.

The Somerville and Chinatown cases speak to how political history shapes public health action. Public health practitioners need to be aware of more than just the diverse sectors that comprise communities. They need to understand the interests, priorities, and politics across and within factions of the community and the history that drives them. Asset-assessments, one on ones, power analyses and base-building strategies used in a community organizing can help to both understand community context while advancing change efforts.

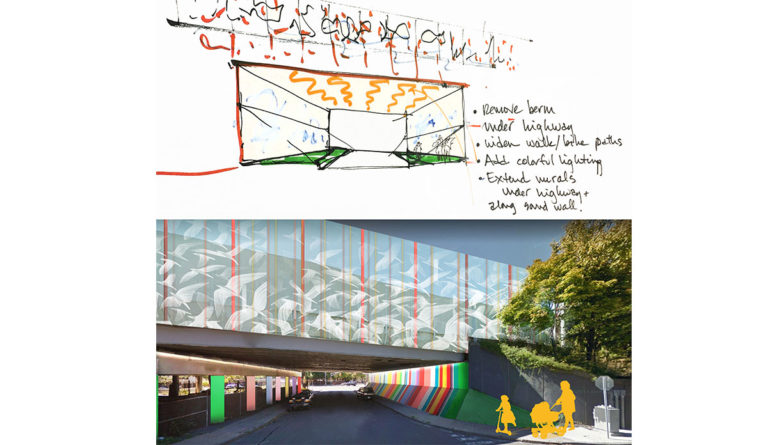

Art Work & Image

Sketch by Michael Grant. Rendering produced by Pilar Botana Martinez, a Boston University School of Public Health Ph.D student in the Department of Environmental Health. With a background in architecture and urban planning, Martinez’s research interests focus on understanding the effects of air pollution, noise, extreme temperatures and other exposures from the built environment on physical and mental health outcomes for environmental justice populations.