When Ideology Clashes With Immunity

Even slight declines in childhood vaccination coverage can cause hospitalizations and other complications to rise dramatically.

Read Time: 2 minutes

Published:

The United States Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has called childhood vaccines “dangerous,” and some state leaders are pushing to lessen school vaccine requirements. Vaccines have long been celebrated as one of public health’s greatest triumphs, most recently with the development of the COVID vaccine under Operation Warp Speed. Yet skepticism has always existed. What is different now, through Kennedy, is that vaccine doubters and deniers have gained an even more powerful platform.

These political shifts are growing alongside rising vaccine hesitancy, fueled by misinformation, distrust in institutions, and a growing skepticism about immunization.

Measles once hospitalized tens of thousands of American children each year, and polio paralyzed more than 15,000 annually before the 1955 vaccine. Thanks to routine childhood vaccinations, these and other deadly illnesses like rubella and diphtheria became rare or disappeared entirely from the United States.

Now, new evidence suggests that these hard-fought successes may be dwindling. A predictive modeling study led by Matthew V. Kiang simulates what would happen if childhood vaccination rates for common childhood diseases (measles, rubella, polio) continue to decline. While it cannot predict the future with certainty, this model—like those used for seasonal flu forecasts and early COVID-19 projections—is a valuable tool for assessing risk and guiding future planning. Using demographic and immunization data from all 50 states, they modeled hypothetical disease spread scenarios across the U.S. over 25 years.

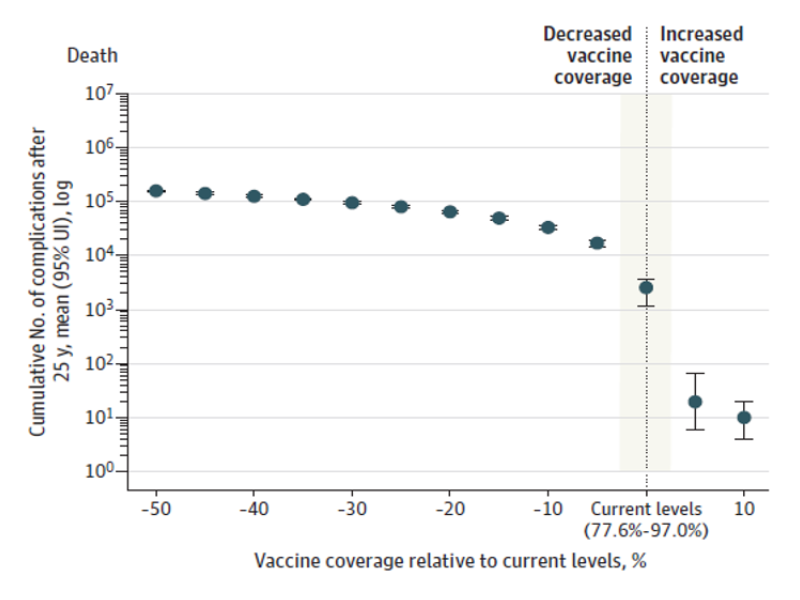

As demonstrated in the graph, as coverage declines, even slightly, hospitalizations and complications rise dramatically.

In an unvaccinated population, one person with measles can easily infect a dozen or more others, making it one of the most contagious diseases known. If vaccination coverage drops by just 10%, the model predicts more than 11 million measles cases. A 50% drop across all four major vaccines could lead to over 159,000 deaths and more than 10 million hospitalizations. By contrast, raising measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) coverage by just 5% could reduce projected measles cases to under 6,000 over the next 25 years.

While the model only makes predictions, these predictions can shape real-world outcomes. One fact remains constant: vaccines have saved millions of lives, and their continued use is one of the most effective tools we have to protect public health.