When Disaster Delays Diagnosis

Natural disasters and health emergencies disrupt preventive care, delaying early detection and treatment of common conditions.

Read Time: 2 minutes

Published:

Colorectal cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the United States. It is also one of the most preventable because many cases are detected through routine screening before symptoms appear. Early detection improves survival rates and reduces the cost of treatment.

During natural disasters and public health emergencies, however, access to preventive care is often disrupted. Power outages, staff shortages, and transportation barriers can force hospitals to close and prevent patients from getting care. Without timely screening, colorectal cancer is more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage, when it is harder to treat. Previous research suggests even a three-month interruption in screening can lead to increased mortality.

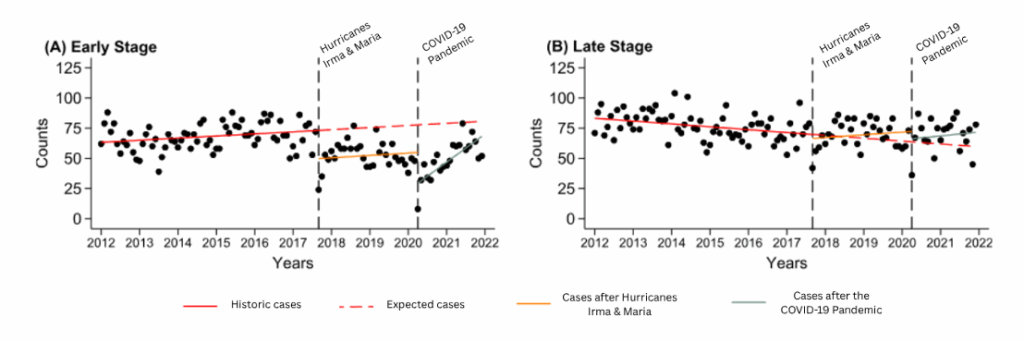

Building on this evidence, Tonatiuh Suárez-Ramos and colleagues examined how Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 and the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 affected colorectal cancer diagnoses in Puerto Rico. They analyzed data from the Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry to track monthly cases from 2012 to 2021.

Overall, new colorectal cancer diagnoses dropped by 17.5% immediately following the hurricanes and 24.2% when the pandemic began. In the 2 years after both events, researchers saw fewer early-stage diagnoses and more late-stage diagnoses than they expected based on historical trends. This shift suggests that some people with early-stage cancer went undetected when screening programs were interrupted and were instead diagnosed later, once symptoms appeared.

The hurricanes and pandemic affected cancer screening in different ways. Even before 2017, Puerto Rico’s health system was chronically underfunded and had limited resources. Hurricanes Irma and Maria further damaged the island’s physical infrastructure. Ninety-seven percent of roads and 28% of federally qualified health centers were damaged across the island, and during the 11 months it took to restore electricity, many hospitals relied on diesel generators. As a result, screening declined more in rural areas, which had fewer functioning hospitals and slower recovery from the damage. During the pandemic, patients were hesitant to seek care, and all hospitals faced staff and equipment shortages, which caused screening to decline uniformly across the island.

The authors urge policymakers to develop disaster response plans that include strategies to mitigate disruptions to cancer care. Because different types of crises affect health systems in different ways depending on location and baseline resources, responses must be tailored to specific contexts. And, as climate change fuels storms and pandemic threats persist, ensuring continuity of cancer screening is critical to protecting population health.