The Real Cost of “Unnecessary Spending”

A new model estimates that U.S. cuts to global aid could result in 9 million more child TB cases and 1.5 million more child TB deaths.

Read Time: 3 minutes

Published:

What looks like a line item in Washington can become an empty shelf in a health clinic thousands of miles away. When global health funding stalls in donor countries, clinics layoff staff, labs run out of supplies, and outreach teams dissolve. For families, this means fewer prevention and screening services, longer waits at clinics, and delayed treatment for diseases that spread fast when health systems shut down.

A modeling study led by Nicolas Menzies estimates the potential impact of this kind of disruption on child tuberculosis in 130 low- and middle-income countries. The team used existing data from the World Health Organization and the Global Burden of Disease study, then applied mathematical modeling to create simulated “virtual” groups of children. In other words, they used data and equations to estimate what might happen to children born each month from 2010 through 2034. They then estimated how many children would be exposed to tuberculosis (TB) and how many would get sick, using country-level data from the World Health Organization and the Global Burden of Disease study.

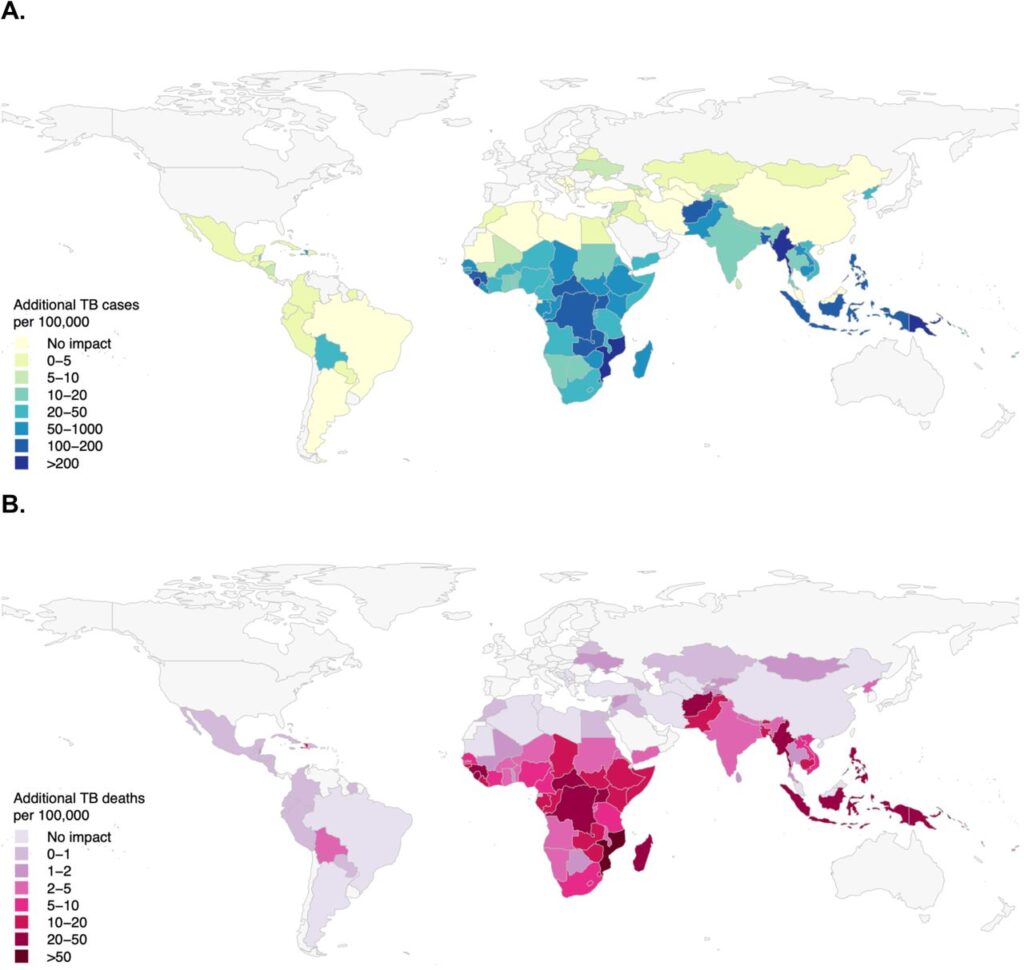

Darker shaded areas on the maps above show higher projected increases in child TB cases (A) and deaths (B) per 100,000 people under the most extreme funding reduction pathway, compared with the historic rates of support. Under this projected funding decrease, the model estimates about 8.9 million additional child TB cases and 1.5 million additional child TB deaths through 2034. Those numbers translate into crowded pediatric wards, more missed school days, and more families facing a disease that is preventable and treatable when health systems are steadily resourced.

The largest projected increases of TB cases cluster in the World Health Organization African and South-East Asia regions. Many of the countries predicted to be hardest hit have a high HIV burden or rely heavily on external funding. When funding drops, TB control can unravel in a predictable sequence: fewer tests and contact tracing, more missed cases, delayed care, and treatment interruptions when clinics face stockouts.

Children are uniquely vulnerable when TB services slip because their disease is harder to spot and harder to confirm. In kids, TB can look like a routine cough or pneumonia, and confirmation often depends on lab testing that may be limited or delayed. Tests also miss TB more often in children, so gaps in follow-up can leave infections untreated and spreading at home.

The map is not fate. It is a warning about what can happen when leaders label global health support as “unnecessary spending.” Keeping TB and HIV services stable, from test kits to community follow-up, can keep funding debates from turning into preventable illness and death among children.