The Microbiome and the Public's Health

Each of us is a living ecosystem with trillions of microorganisms living on and in us, our microbiome. Each of us has her own collection of such microbes, inhabiting skin, mouth, gut, lungs.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

The Microbiome and the Public’s Health

Each of us is a living ecosystem with trillions of microorganisms living on and in us, our microbiome. Each of us has her own collection of such microbes, inhabiting skin, mouth, gut, lungs. Yes, it’s surprising that identical twins are barely more similar to one another in microbial composition than are non-identical twins; that our personal menagerie changes over time; that a sufficiently extreme short-term dietary change can cause the gastrointestinal flora of different people to resemble one another within days. Yes, the microbiome may well turn out to play a critical role in an individual’s health, a very intriguing prospect. But when nearly two dozen federal agencies—NIH, FDA, EPA, NSF—join together to release a five-year strategic plan to bolster the study of microbiomes, we wonder why these same agencies can’t get together on another day to make a second strategic plan. This one a plan for public health, not private health, one that could save lives and reduce morbidities next year by focusing on what we know matters to our health: the policies that drive behavior.

We are at that moment in a relatively new scientific field when everything seems to influence it; the microbiome’s composition is altered by sleep, stress, exercise. We, who work far from the basic science lab, believe it would indeed be meaningful if someday that by controlling our behaviors, we might know how to control our personal microbial community and thus our health. Yet a “personalized” microbiome remains a distant and unlikely dream.

We agree with our microbiomist colleagues that our environment, from the personal to the atmospheric, matters. And that our social networks, with whom and how we interact, matter too. But we would prioritize attention to the known drivers of longevity and quality of life for today’s population—poverty, insurance gaps, homelessness, the broad distribution of preventive services—hard problems that we can change and that would benefit from strategic health planning. We are envious that the microbiome brought 23 federal agencies together in common cause, even if their report included the usual recommendations: share data, make access to data easier, collaborate, and expand the number of studies.

Let’s appreciate microbiome research for what it is—pure, joyous, creative science that may produce fascinating new findings in a decade or two and in the meantime a workforce development venture for young scientists. But let’s collaborate on equally hard macro-level puzzles that may better and sooner benefit the public’s health.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

THE NON-USE OF THE ANNUAL CHECK-UP

The need for an annual physical remains controversial. But in 2011, Medicare introduced the “annual wellness visit” for seniors to encourage evaluation of fall risk, dementia screening, vaccination, and other preventive services that older Americans don’t receive often enough, and primary care providers often neglect. This study demonstrates that in 2014, only 16% of Medicare beneficiaries had an annual wellness visit. Some doctors performed these examinations much more than others, and white seniors and those with higher incomes were more likely to be the recipients. Whether such visits improve health remains to be seen.

HELP WITH HOUSING HELPS IN UNEXPECTED WAYS

Of the 24,000 youth aging out of the foster care system in the United States each year, around 36% will experience homelessness. New York City affordable housing and supportive services program (NYNY III) began to provide supportive housing for at-risk transition-aged youth in 2007. After at least seven days in the program, NYNY III participants aged 18 to 25 experienced greater housing stability for at least two years, and were also less likely to acquire a sexually transmitted infection. Housing programs are effective for more than just reducing homelessness.

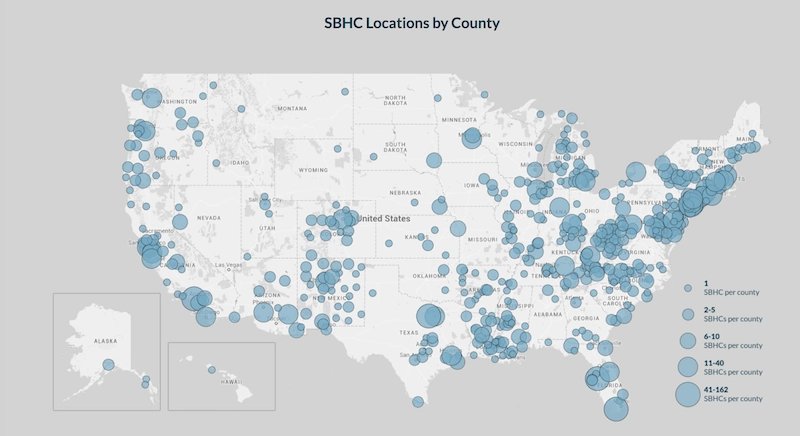

SCHOOL-BASED HEALTH

School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) play a unique role, bringing health care to a place where adolescents consistently spend about eight hours a day. The location and availability of the services of SBHCs can reduce disparities both in health and education, especially for children from a low-income background or of a racial minority group. As of 2014, there are 2,315 SBHCs.

Education and health are intrinsically linked. SBHCs promote academic success by addressing health problems that would otherwise impede a student’s ability to prosper. SBHCs provide a wide variety of services ranging from preventive services to oral health to behavioral health that vulnerable students are often not able to access due to transportation or financial barriers.

John Knopf and colleagues at the Community Preventive Services Task Force from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) found that SBHCs have positive influences on both health and education outcome measures. SBHCs reduce rates of school suspension and high school non-completion, as well as increase GPAs. Knopf et al. also found a decrease in emergency department and hospital visits, increases in immunizations and preventive services, and more children with a regular source of health care.

Map from School-Based Health Alliance 2013-14 Digital Census Report