Missed Opportunities: Gaps in Cancer Screening Among Men Living with HIV

For men in the South living with HIV, seeking anal cancer screening is deeply inequitable, with age and partner gender playing key roles.

Read Time: 2 minutes

Published:

Anal cancer, primarily caused by persistent HPV infections and closely linked with HIV, has been on the rise in recent years.

When screened and detected early, anal cancer has a relatively good prognosis (with a 70% 5-year survival rate). The primary screening method is a relatively quick anal pap smear. Formal screening guidelines have yet to be adopted, though. Without formal guidelines, providers may not view screening as necessary, leading to inconsistent screening practices and missed opportunities for early detection.

People living with HIV (especially men who have sex with men) are 30 times more likely to have anal cancer than those without HIV. In the United States, Southern states account for 52% of new HIV diagnoses. Given these trends, it is essential to examine how anal cancer screening is carried out in this region.

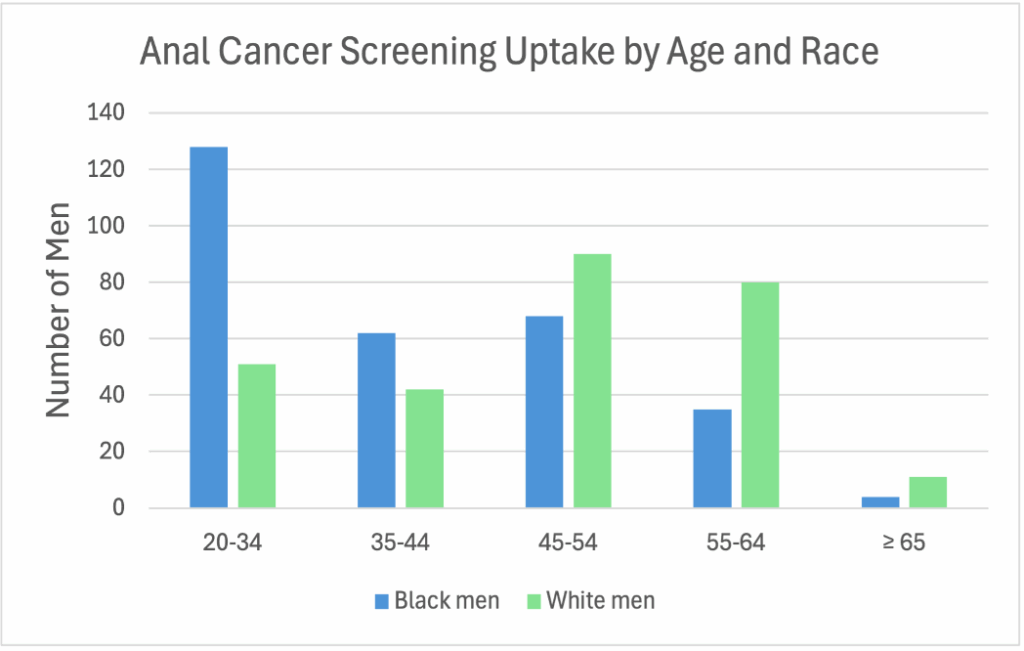

A recent study looked at factors linked to cancer screening among 1,114 male patients at a large HIV clinic in Alabama. Patient medical record data, including age, race, and sexual history (condom use, partners, etc.), were analyzed to understand who was most likely to get screened.

Anal cancer screening among men living with HIV was affected by multiple factors, but partner gender and age had the greatest influence. Men with female partners were 96% less likely to be screened compared to men with male partners. Younger men (aged 20–34) were almost five times more likely to be screened than their middle-aged counterparts.

Social vulnerability also influenced screening disparities. Counties with greater social vulnerability had fewer screenings, with Black men, especially those in their mid-fifties and older, having the lowest screening rates. Socioeconomic and structural barriers, such as poverty, transportation barriers, and underfunded facilities, compound these disparities across the South. In addition to the poor infrastructure, there are several restrictive policies in place that make receiving sexual health care in the South difficult.

For men in the South living with HIV, anal cancer screening is deeply inequitable. Advancing equity in this region requires adopting clear screening guidelines, focusing outreach on under-screened groups, and addressing structural barriers that improve screening and care.